Source: Abdulkareem Mojeed

Polluted cassava farm land in Ibeno, Akwa Ibom state

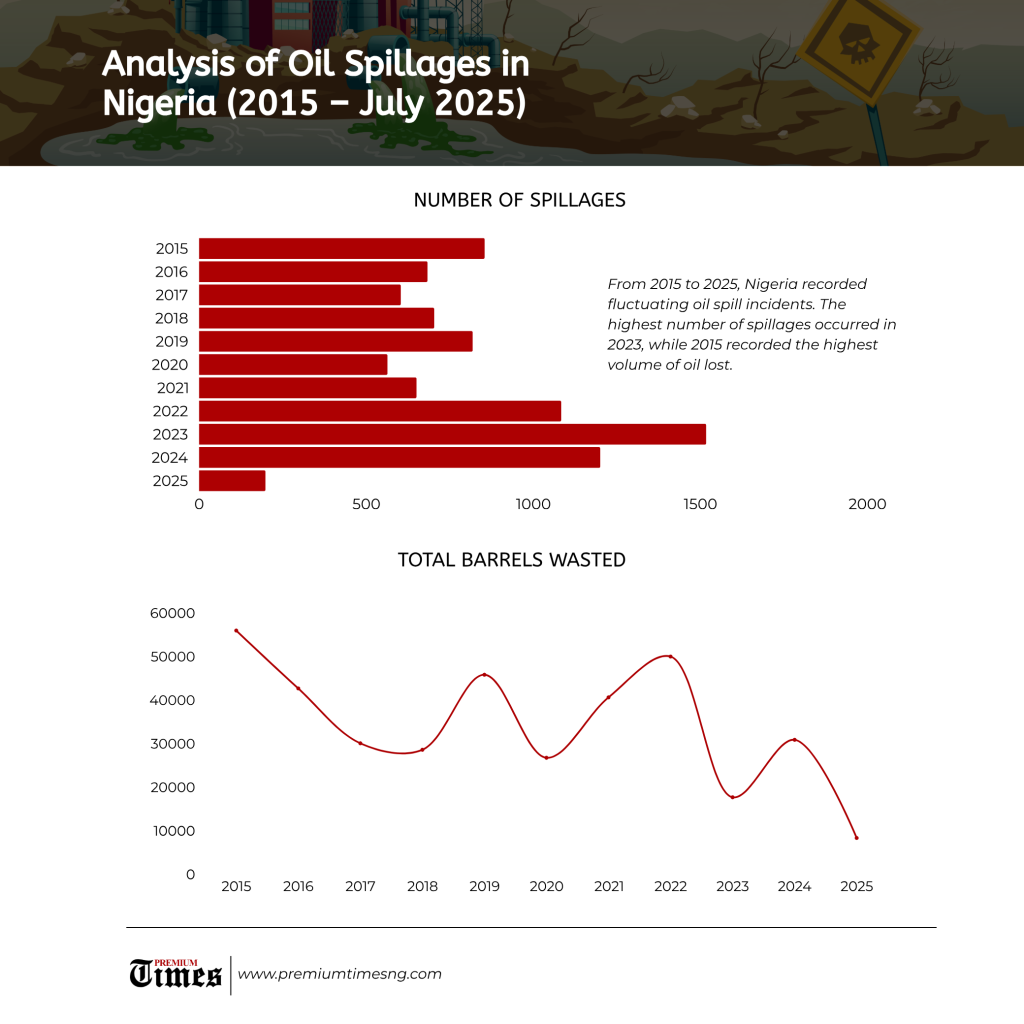

Data published by the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA)—a Nigerian government agency monitoring oil spills—reveals that over 9,890 incidents were documented across Nigeria between 2015 and July 2025

On 6 May, a Trans Niger Delta pipeline carrying crude oil burst at B-Dere, a community in the Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State. The incident forced Daniel Kpoobari-Bani, his wife, and their four children to leave their home quickly to escape the flammable oil gushing out of the ruptured pipeline a few meters away from their front door.

Mr Kpoobari-Bani, a resident of B-Dere whose compound was flooded by the spilling crude oil (Photo Credit: Abdulkareem Mojeed)

“My compound was affected by the leakage,” Mr Kpoobari-Bani narrated to PREMIUM TIMES during a visit to the community at the time. “We have been in discomfort since the incident occurred.”

Workers from the Shell oil company stopped the spillage on 15 May. This reporter observed as two tanker trucks sucked up the oil with long hoses as a humming bulldozer cleared a pathway for them. Armed soldiers stood at strategic positions as residents gathered to watch the operation.

Ruptured Trans Niger Delta pipeline spilling crude oil

Before the arrival of the workers, residents were scooping up the flowing oil into buckets and jerrycans. The air was thick with the choking odour of crude oil. Cooking became hazardous due to the risk of explosion, forcing many residents to relocate from their homes.

Before the workers fixed the ruptured pipeline, PREMIUM TIMES observed that the soil and crops in the surrounding farmlands had absorbed the crude content, and the environment was polluted.

Polluted farmland due to ruptured pipeline at B-Dere community in Rivers state( Photo credit: Abdulkareem Mojeed)

The leaflets and pseudostems of cassava, cocoyam, banana, and plantain—a major staple crop grown by community residents—looked greasy and dripped with oil. Some residents who scooped up the crude oil had hidden it in the crop fields.

“Shell needs to relocate us from here,” Mr Kpoobari-Bani told PREMIUM TIMES, recalling a similar leakage two years earlier. “Crude oil has destroyed our crops, and we can no longer drink the water from our wells.”

The residents of Ogoniland and other oil-producing areas in Rivers State have a history of protesting against the deleterious impacts of oil production on their natural environment and livelihoods. Their protests have occasionally been met with repression by the government.

In the 1950s, Nigeria discovered crude oil in commercial quantities, eventually becoming the 15th-largest crude oil producer globally and the largest in Africa. Oil exploration and production in the country have predominantly been in the Niger Delta region.

However, many oil-rich communities, such as Ogoniland, suffer hydrocarbon pollution. Many residents whose primary occupations are crop farming and fishing can no longer access farmlands and water, due to continuous oil leaks from creeks and pipelines.

The May spillage in B-Dere was one of the latest episodes of environmental degradation in Ogoniland. Extensive fossil fuel pollution has been recorded in the area over the past three decades, forcing the Nigerian government and the relevant stakeholders to initiate a $1 billion cleanup and restoration programme in 2018. The programme followed a comprehensive study conducted by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2011.

The remediation/restoration effort is being carried out by the Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP), an agency of the government domiciled at the Federal Ministry of Environment.

However, the impact of the cleanup initiative remains largely negligible, as major oil pipelines traversing these communities frequently leak, resulting in spills that continue to harm the environment.

HYPREP did not respond to an email sent to the designated address on its website for comments on our findings.

However, according to data published by the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA)—a Nigerian government agency monitoring oil spills—over 9,890 incidents were documented across Nigeria between 2015 and July 2025.

Analysis of Oil Spillages in Nigeria (2015 – July 2025)

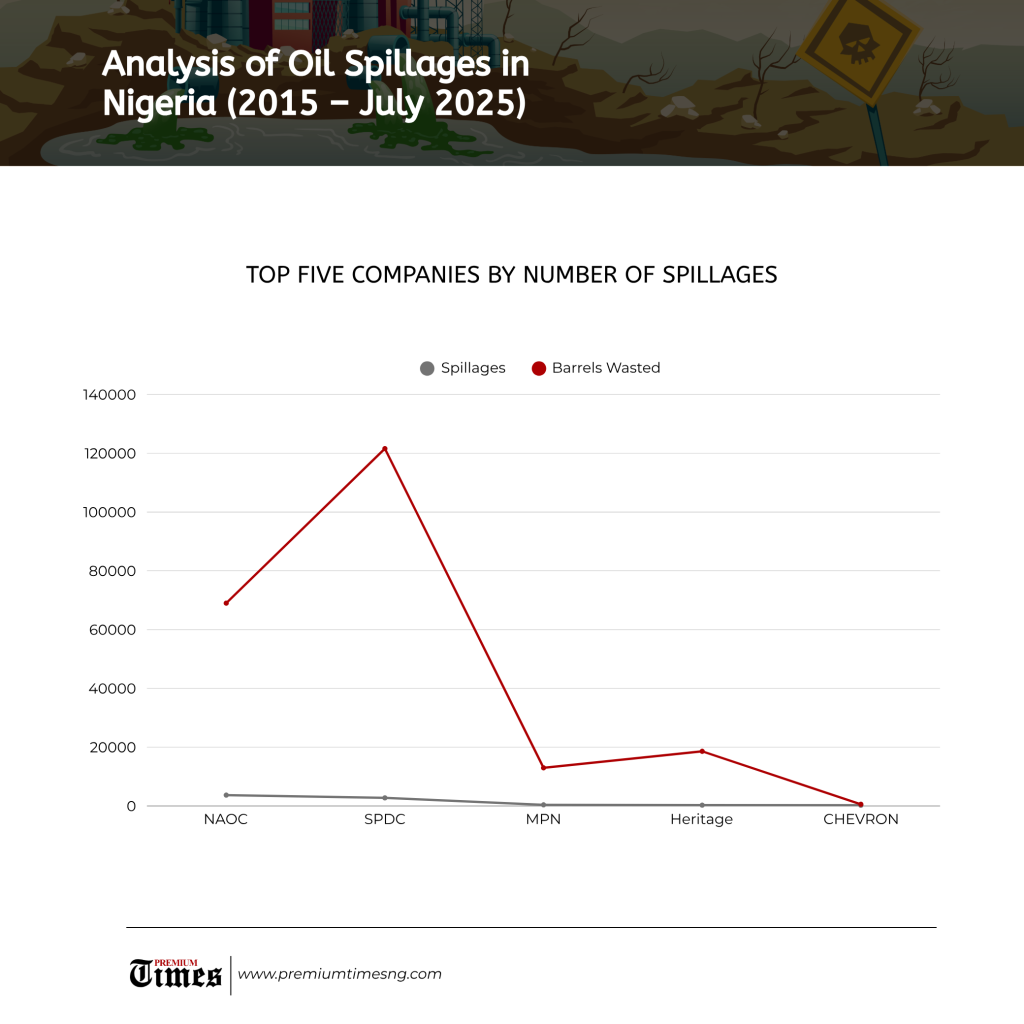

The data reveals that the highest number of spillages occurred in 2023 (1,518), but the highest volume of crude spill was in 2015 (nearly 56,000 barrels). NOSDRA’s oil spill monitoring report states that Rivers State recorded the most spills with 4,184 incidents, followed by Bayelsa (2,118), and Delta, Akwa Ibom, and Imo with 1,589, 399, and 272 cases, respectively. The data attributes the predominant cause of oil spills to sabotage. Other significant causes include corrosion and equipment failures.

Analysis of Oil Spillages in Nigeria (2015 – July 2025)

The B-Dere spill was blamed on “equipment failure” by a company identified as “RENAISSANCE.” This probably refers to Renaissance Africa Energy Company, a member of a consortium that recently acquired Shell’s Nigerian subsidiary, SPDC, in a significant transition in Nigeria’s oil and gas sector. The consortium includes ND Western, Aradel Holdings, FIRST Exploration, and Petro. The group did not respond to an email seeking its comments on our findings.

Approximately 100 barrels (15,900 litres) of crude oil were spilt in the B-Dere pipeline rupture, as detailed by NOSDRA data. NOSDRA said, “A rough-edged hole, approximately 10 cm in diameter, was discovered on the pipeline at the 6 o’clock position.”

However, community members believe the volume spilt was much higher. They said the spillage began on 6 May and was not contained until 15 May.

Moreover, environmentalists have argued that pollution and environmental damage caused by oil spills in Nigeria have never been adequately assessed, and the affected communities and individuals are mostly not compensated.

“Some Shell officials took pictures of the environment where the spillage occurred recently, and they took my name and that of my mother. Then they asked us to wait until they get back to us,” Mr Kpoobari-Bani told PREMIUM TIMES when contacted in late July.

Five years ago, Gbarale Joy abandoned the farms where she grew cassava, corn, vegetables and melon in her hometown of Sii, due to incessant oil spillage.

“If we plant seeds, they rot. When my cassava reached the stage of uprooting, I couldn’t find anything underground. Even the stems rotted,” she told PREMIUM TIMES in May.

“We get seafood from this saltwater, but we can’t find any of these in the water anymore. We used to have periwinkle and other aquatic life from the water, but you can’t find them anymore due to these spills.”

On a Tuesday morning in May, Sylvanus Omotoye, a fisherman at the Ibeno beach terminal in the oil-rich Akwa Ibom State, sat on a cross brace of his wooden canoe to prepare his fishing nets for the day’s expedition.

“Due to the effects of oil spills on the water, we have experienced a significant decline in fish catch over the years,” said Mr Omotoye, who has worked in Ibeno for nearly 50 years. “Some fishermen have migrated to Cameroon.”

Ibeno, alongside Mbo and Eastern Obolo, is a key oil-producing local government area in Akwa Ibom. Communities like Ikot Abasi, Onna, and Esit-Eket are also recognised for their significant oil and gas production.

Ibeno hosts leading oil and gas exploration companies, such as Seplat Energy Limited (ExxonMobil). The community residents engage in fishing and crop farming. The farmers cultivate crops such as yams, cassava, cocoyams, corn, banana, and plantain, among others.

“Oil spill has reduced my catches significantly, and destroyed my fishing nets,” said a fisherman. ‘’We didn’t usually travel far into the sea to make catches in the past, but now that is not the case,’’ he said.

Some environmental justice activists in the region believe the government and the oil companies are not committed to addressing the issues.

“Oil spill has brought untold hardship to farmers across the Niger Delta. Oils have penetrated the soil for over 70 years. Their crops decay upon harvest. Most of the farmers are on loans,’’ said Umo Isua-Ikoh, coordinator of the Peace Point Development Foundation (PPDF), an environmental Justice advocacy group working in the region.

He said farmers take loans to invest in their farms, but often cannot repay.

“When they come to harvest, they get nothing from their field. Already, they are in debt. Some have developed hypertension or even run away,” Mr Isua-Ikoh said.

“The Ogoni clean up has been going on for over 10 years, yet no impact. It is supposed to be a model for cleaning up the Niger Delta, but if they are still struggling with that for many years, when will it get to Ibeno? It is a big challenge,” he said.

The activist accused the government of colluding with the International Oil Companies (IOCs) against local communities.

“All that they will be talking about is palliatives. Even when the palliatives come, they fall on the table of the politicians. So the people impacted are not benefiting,” he said.

Like Mr Isua-Ikoh, John David, an Ibeno high chief, said the government and IOCs did not act over several spills reported to them.

“Many oil spills have been happening. NOSDRA and DPR will come, but at the end of the day, you will not hear anything about it. Politicians, governors, and commissioners would come whenever there is an oil spill and address the community, but uptill now, nothing has been done,” he said.

An environmental justice campaigner, Nnimmo Bassey, noted that pipelines have lifespans and are to be replaced when they expire. He added that the oil companies have the responsibility to keep their facilities secure and in good condition.

“We hardly see that happening in Nigeria,” he lamented.

Mr Bassey, who is also the director of HOMEF, explained further that oil wells also have lifespans, just like mines for solid minerals, and should be decommissioned before being abandoned at the end of the lifespans.

He said in Nigeria, the first oil wells drilled in the 1950s were abandoned in the 1970s without being decommissioned.