Source: Gbemidepo Popoola

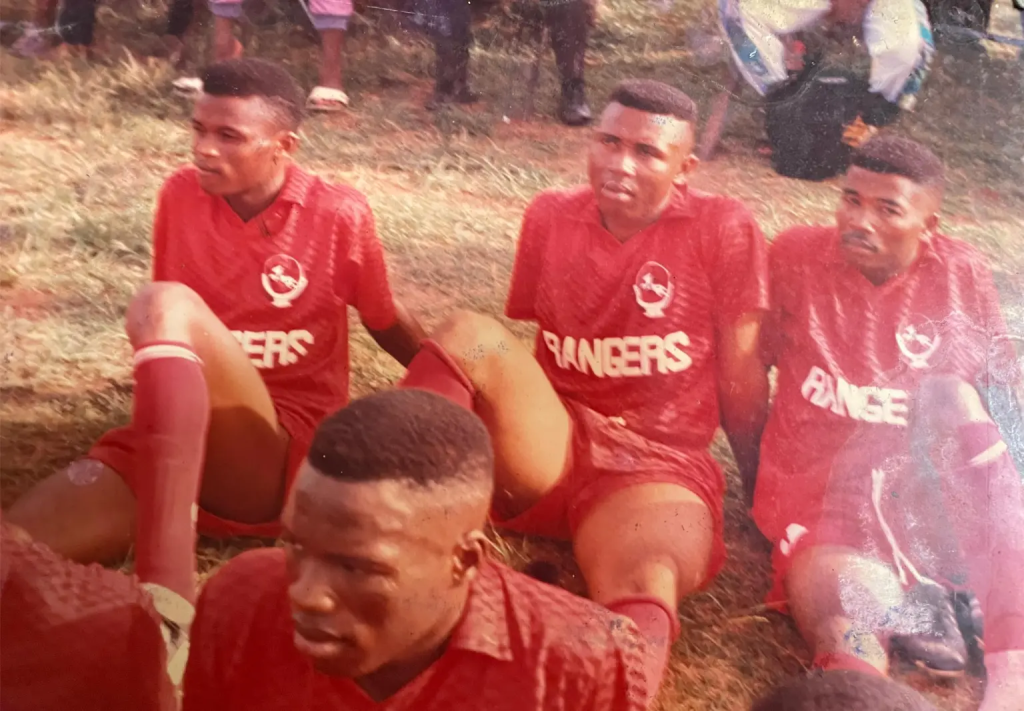

Igeniwari George with U-17 teammates (Photo Credit: George Family)

Three decades after Rangers teenager Igeniwari George was shot dead, leaving an FA Cup match in Ibadan, his story remains unfinished.

In February 1979, Port-Harcourt welcomed a son into the George family. His name was Igeniwari.

The George household breathed football. His eldest brother, Perekebina, played at the grassroots level. Alari, the second, was a grafter in midfield who wore the colours of Sharks FC, later NAPC of Warri, and even moved to Cameroon for football.

Then came Finidi George, who would etch his name in Nigerian folklore: Super Eagles winger, AFCON 1994 champion, and Champions League winner with Ajax.

Igeniwari, the youngest, absorbed it all. Watching his brothers step onto pitches gave him a mirror of what he wanted: to belong to the game.

“He was the calm one in the family, very talented yet, very respectful. Football was his language.” Igeniwari’s elder brother, Alari, told PREMIUM TIMES in an exclusive interview.

At Enitonia High School, Port Harcourt, Igeniwari’s potential began to surface. He trained and played alongside boys who would later become household names: Victor Ezeji, one of the most decorated players in the Nigerian league, and Albert Yobo, older brother of future Super Eagles captain Joseph Yobo.

The trio were ambitious. By 1994, their talent caught the attention of coach Monday Sinclair (The Professor), who was preparing to take charge at Rangers International of Enugu. Sinclair brought Yobo and Igeniwari to Rangers, while advising Ezeji to be patient.

For a Port Harcourt teenager, this was a seismic leap. Rangers weren’t just a club; they were an institution.

By 1995, Igeniwari’s rise was undeniable. He was called into the Nigeria U-17 squad and travelled with the team to the FIFA U-17 World Cup in Ecuador.

For a player his age, this was more than just a tournament. It was a shop window. Scouts and agents from Europe combed the stands, hunting for the next teenage star. Some of Igeniwari’s teammates from that generation would go on to secure contracts abroad. He looked set to join that trajectory.

The boy from Port Harcourt had stepped onto a world stage.

On their return, Rangers had an FA Cup quarterfinal clash against Stationery Stores of Lagos in Ibadan. It was not just another game. The Rangers–Stores rivalry was fierce, soaked in history and tribal pride.

The match was tight. In the 87th minute, Rangers won a controversial penalty. It was converted. Final score: 1–0.

The aftermath turned violent. Stores’ fans invaded the pitch in protest. Police moved to secure the players, hustling Rangers into their team bus to leave the stadium. Igeniwari was one of those who got onto the bus, going on to sit at the back in his usual simple, quiet manner.

Then, as the bus pulled away, a single gunshot pierced the chaos.

The bullet struck Igeniwari George in the back.

As Alari would describe the events leading up to the incident, in his words; “He got there the day before. But he had premonitions, as he didn’t want to go for the game. But, we encouraged him to go, so it won’t look like he was being proud due to having represented the country at the U-17 World Cup, just days apart.”

No one around him was prepared for or saw what was coming ahead.

Igeniwari (far left) in Rangers colours (Photo Credit: George Family)

He was rushed to a nearby Ibadan hospital. But what followed exposed a tragedy larger than one boy.

According to simultaneous accounts, the hospital was unable to perform emergency surgery because there was no water.

Igeniwari bled out. His life ended in the casualty ward. He was 16 years old.

The ex-Sharks man, just like his younger brother Finidi George, spoke about the incident in words.

“It was a day after he left for Ibadan, that he died after being shot in the spine from the back. Due to the chaos that ensued after the game, and the failure of the Nigerian healthcare system.”

Who fired the shot?

Was it an angry fan outside the ground? A misfired warning shot from police? A stray weapon from the melee? Thirty years on, there is no official clarity.

No transparent investigation has been published. No judicial inquiry has laid out the facts. The George family, and Nigerian football, have lived with deafening silence.

This absence of closure is more than painful; it is systemic. It reflects how Nigerian sport has often swept its darkest nights under the rug.

When asked about whether there were any official explanations or inquiries opened, Alari’s response was;

“Till this moment, we never got an official explanation; nothing from the NFA (NFF) as they were formerly called, nothing from the league body. If it was a stray bullet from the police trying to restore order and protect the players, or if it were an overzealous Stores fan.”

No closure, no inquiries, even after 30 years.

The Georges embody Nigerian football’s double-sided coin.

On one side, Finidi George ascended to the pinnacle: Ajax, Real Betis, Mallorca, and the Super Eagles. On the other hand, Igeniwari’s story ended in anonymity, his career clipped before it began.

The contrast is cruel. One brother lifted the Champions League; the other died on a stadium road because a hospital could not provide water.

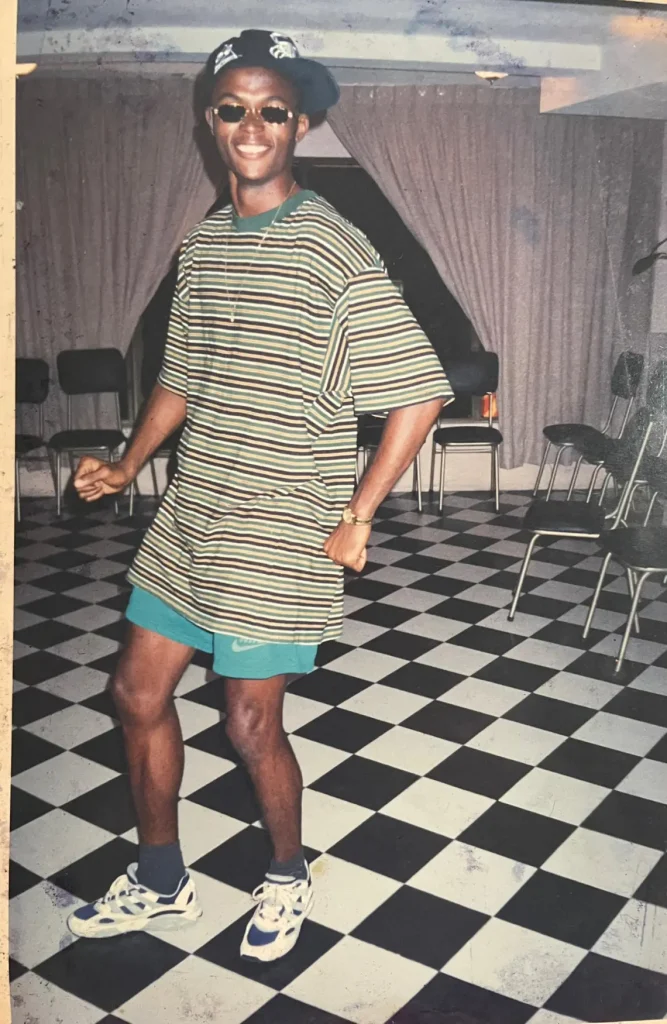

Igeniwari George was full of life (Photo Credit: George Family)

Igeniwari’s death is not just a family tragedy. It represents two endemic failings of Nigerian football in the 1990s, and in many ways, still today:

Poor crowd control and stadium security; high-stakes matches often lacked clear protocols for segregation, evacuation, or player protection.

Inadequate medical preparedness; too many Nigerian stadiums had no standby ambulances, trauma kits, or functional links to hospitals.

These failures turned a single bullet into a fatality. They continue to haunt Nigerian football every time a fan or player suffers an avoidable tragedy.

While Nigeria parades its winners, parades for AFCON triumphs, welcome ceremonies for foreign-based stars, the country rarely pauses to remember those it lost.

There is no annual remembrance for Igeniwari George. No youth tournament in his name. No national inquiry that closes the book on what happened in Ibadan.

Forgetting has consequences. Without institutional memory, there is no pressure for reform.

During the interview, Alari narrated how he was devastated and even locked up by the government of the time.

“I was very sad and devastated, breaking down multiple times; don’t forget that it was during the military era, and there was little anyone could say. I was even locked up by the military on the day of the burial, I could not witness my brother’s burial live.”

Also, going further to state for a fact that his brother’s burial could have been better done.

“I did not like the way his burial was handled; we could have done it better if it were a private burial by the family. But, because of the services he had rendered to the nation, it became a state one; that wasn’t befitting.”

The counterfactual: what might have been

What would Igenewari have become?

History offers clues. Players who featured at U-17 World Cups often carved out long NPFL careers, some moved abroad, some wore the senior Eagles jersey. He had the technical schooling, the exposure, and the network of peers, elder siblings and a trusted coach, Monday Sinclair (The Professor), to sustain a professional life.

That possibility, a decade or more of NPFL contribution, maybe even a Super Eagles call-up, evaporated the moment the bus left the stadium in Ibadan for redemption in healthcare.

Igeniwari George stands tallest amongst his peers (Photo Credit: George Family)

This year (9th September) marks 30 years since Igeniwari George’s death. It is more than a milestone. It is a test.

Has Nigerian football built the safeguards that could have saved him? Are ambulances mandatory at all major matches? Do hospitals around major stadiums have protocols for emergency surgery? Do police still fire live rounds at stadiums during unrest?

The honest answers remain uncomfortable.

Commemorating Igeniwari should go beyond sympathy. Three reforms would honour him better than any plaque:

Mandatory medical teams, at every competitive match, with minimum equipment standards.

Independent safety audits of stadiums before hosting matches.

Transparent inquiries into any stadium death or injury, with reports made public.

These are the reforms that attach accountability to memory.

For Finidi, for Alari, for Perekebina, and the youngest son, the loss was not abstract. It was a brother, a son, a teammate.

As Alari puts it;

“We can never get over it, in its totality. He was such a promising, humble young boy who had the world at his feet. We still need answers, that sadly might never come.”

Until those answers come, the family’s grief is also Nigeria’s unfinished business.

Nigeria is a footballing nation. But to be a great football nation is not only to celebrate goals. It is to protect its players, to account for their deaths, and to reform when systems fail.

Igeniwari George was more than a victim. He was a mirror, showing us what Nigerian football looked like at its most vulnerable.